Dear Reader;

I have waited a long time to tell this story. Some things become easier with age, some do not. I hesitate even now, but I believe it is time.

We are entering an era upon the Earth when the only way forward is to be brutally humbled as we confront oppositional truths. This means letting go of the need to be right and righteous. It means letting go of making others wrong. It means finding a way forward in a willingness to question everything and defend nothing, and by so doing, acknowledge that human life is overflowing with contradiction, and the way to clarity is found through integration, rather than opposition and elimination.

Within this agonizingly confronting principle, I will state my premise. Abortion is indeed murder. And at times, murder is a choice which must be made. Let us tell the truth, and let us not be afraid.

I say this as a woman who had an abortion forty years ago, in the unalterable recognition that on that day I participated in ending a life.

In order to truly address this great debate, we must be able to tell ourselves the truth, and from truth make our decision, beyond politics, beyond religious fundamentalism, beyond feminist rhetoric, and beyond medical doctrine. Every woman must make a decision of the soul, and it’s time we understand that nothing less will do.

Rumi authored a particular poem which is often quoted from a translation by Coleman Barks as: "Out beyond the ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I'll meet you there. When the soul lies down in that grass, the world is too full to talk about.”

Islamic scholars suggest that a more accurate translation may be: "Beyond Islam and unbelief there is a desert plain. For us, there is a passion in the midst of that expanse. The knower of God who reaches there will prostrate in prayer. For there is neither Islam nor unbelief, nor any 'where' in that place."

This latter translation brings us much closer to the framework of Rumi’s faith, and it’s understandable that some object to the simplification of the Western translation, but it seems clear to me that one way or another, Rumi was referencing an indisputable state beyond the constructs of human morality, religious or otherwise. A place of divine reckoning wherein we are granted the opportunity to bow to knowledge, forces and forgiveness beyond our human fears.

Not only is this an idea so radical that most find it difficult to conceive, but even those who may grasp it may be challenged to live in such a rare surrender. We humans want so badly to designate what is wrong, so that we can convince ourselves that we are right. We need the certainty of judgement to feel better about ourselves, and to rise above the horror of the unknown. Indeed this young-soul, black-and-white comfort zone is the foundation of our entire Western judicial and penal system. There is a fine line between justice and vengeance.

But if there is one awareness which may bring a new measure of peace to our turbulent world it would be this: the great questions of life hold no easy answers. Personal fragility often masquerades as moral certainty, and even some of the most grave and shocking shadows of human existence may have their purpose when we view our cyclical lives as a series of lessons leading to expanded consciousness.

We don’t make things right by making others wrong. We come to ascension, to our highest view through the willingness to see all sides. In fact, we heal our fractured selves precisely through the dance of duality, which is never a mistake, no matter how dark, how brutal the opposition. Every moment holds a meaning under heaven.

In our hurry to be righteous, we create separation, and whenever we create separation we push everyone further away from a mutual wisdom. This has been the history of our species. As a collective, however, we are evolving, and thus so many oppositional issues are being brought to the surface of our awareness right now, precisely to grant us this possibility. To meet one another upon that desert plain, beyond belief or unbelief, a place where only a neutral and exalted wisdom resides.

At twenty-four I was an English Lit grad with my first novel picked up by a major literary publishing house, a rare feat even in those ancient times. I was living in my parents’ basement, sustained by a writer’s grant, when an old boyfriend stayed over for one night. He was on his way to England and it seemed likely we would not meet again. I had been abstinent for months and that night was nowhere near the fertile time in my cycle. I knew my body well, and was puzzled when my period was late. I went to a clinic and the nurse confirmed that I had indeed conceived through that solitary act of lovemaking, explaining that initiating sexual activity after a dormant phase can stimulate ovulation unexpectedly. Who knew.

I remember exactly where I sat in that office, how she left the room to complete the test and returned, her eyes cast downward. I remember when she finally spoke, the instant shock that tore through my body and how she mechanically offered tissues. I had no words and felt I was in a dream.

Everything in my life suddenly seemed impossible. My ex was gone, and though he was a lovely soul, we both knew we were not a long term match, and he was in no position to offer financial support. I was a starving artist with big dreams. I wanted marriage and children very much, so much so that the irony of my situation seemed unbearable.

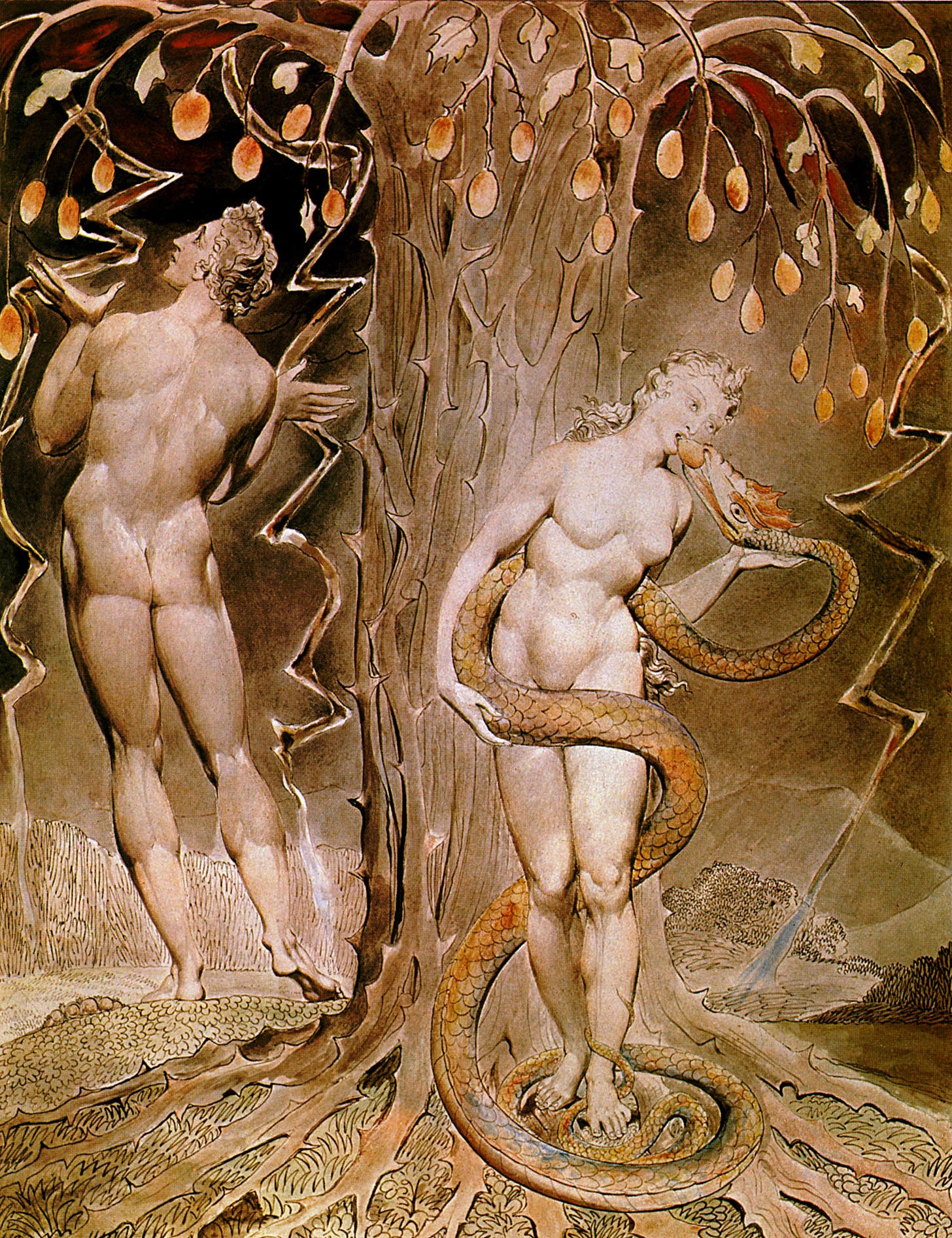

It is not easy to describe the sensation of feeling that one’s entire future has been stolen overnight, as a result of simple affection and sexual connection. There was something deeply familiar in that suffering, cellular memories of shame and punishment. I said yes to the snake. I ate the apple. I was out of the garden forever.

It was a kind of entrapment I had never felt before. Always an outsider, I still managed to function within the expectations of my culture, my tribe. This was not the 1940’s and I would not be sent to a home for unwed mothers, but I still lived in the echo of that judgement. In particular my inability to survive financially on my own was terrifying. I was blessed beyond many in that I had parents whom I knew would not abandon me, but my shame would be their shame. I felt that I had not yet left my own youth behind, and to suddenly become a parent would make me profoundly dependent upon my own. That fear might have been the greatest of all.

I would like to be able to say it was a difficult decision for me, that I lay awake for days agonizing, but I don’t remember even feeling that I had a choice. I did allow myself a brief glance at some ads for baby clothes, but quickly turned away. My salvation seemed to live in the not knowing. From the first moment, the terror of my situation was so great, I didn’t allow myself to believe that I actually carried life in my womb, or to feel its presence. I absolutely disconnected from my body and from the experience. I just wanted to reverse time. I told no one and hoped that I never would.

At the time abortion was legal in Canada, but it was quite a process. An application had to be made, and that application was placed in front of a panel of medical practitioners who would either grant, or withhold permission. Factors involved in their decision were age, health and a previous abortion history. As I was very early on, the nurse assured me that it would likely be approved, but it meant weeks of waiting. I held within me something I had always wanted but could not have. An impossible task lay before me. Every day, every hour, every minute was too long, and the idea of waiting weeks was unbearable.

Somewhat reluctantly the nurse offered me contact information for a clinic in Buffalo, New York. She said she had heard it was a good place. My parents were still away and I believed I could accomplish this without telling them. There was only one person I trusted enough to ask to come with me. For their own reasons, they said no. I went alone.

I pause my story here to interject context. In the forty years since this took place, I have been pulled, magnetically, utterly, into pursuits of spirit and consciousness. I had rejected the casual Anglican affiliation of my family in my early teens, dabbled in atheism, then agnosticism and finally the faiths of the world. When I was visited by a spontaneous intuitive awakening in midlife, matters of spirit became my life. For years now, my every day has consisted of serving individuals with understanding the deepest threads of their karmic journey. I have learned much about individual wounding, patterning and dharma. I now understand the teachings inherent in great suffering. But at twenty-four, I had absolutely no idea.

Every soul chooses a particular flavour of suffering, and none of it is random. What is my greatest pain will likely not be yours, but for each of us, our shadows will lead us to the light, as we surrender, when we allow. Without becoming too entangled with intersecting stories, I will simply say that my own soul wounding is deeply marked by my relationship to mothering, children, birthing and nurturing, and the shadow of these experiences. Child-bearing loss, grief, guilt and shame have figured strongly in my life, over and over again. This is the theatre of my soul’s exploration, as I have been repeatedly pulled into moments of trauma and awakening. With the initiation of this particular experience, I was not entirely an innocent, but truly, I had just begun.

When I packed myself into my $200 vintage MG and headed across the border to an unknown abortion clinic, enough borrowed cash in hand to pay for their services, I was running blind from an unconscious fear. I wanted children so deeply, but not this way. In fact, this made it seem as if everything I had ever wanted would be lost. I had just barely made it out of an adolescence rife with family conflict about my sexual nature. To mess up this badly in the eyes of my family and community would have left me trapped in such dependency that it would have felt like being buried alive. I could not even imagine a way out. I would not allow myself to connect with the idea of a life within me. I successfully numbed that part of the equation. I just wanted to wake up from this terrible dream.

The waiting room at the Buffalo clinic felt like a scene in a Fellini film. It was filled with young girls, heads bowed, voices low. Kids really. Teenagers with their mothers at their sides. The mothers were the ones checking in with the nurses, paying for the procedure, whispering seriously into the ear of the daughter who sat, eyes on the floor. Everyone seemed transparent to me, like a mirage. I was definitely the oldest patient in the room, and the only woman there by myself. Everyone looked away.

In time I was called into a meeting with a counsellor who asked a few questions. Did I understand what was to happen. Was I sure about my decision. Did I need to talk to someone afterward. Yes, yes and no; all lies. I wanted very much to not talk, to not think, to not know. There was a hint of kindness in her eyes, and I could not let myself feel it. I had to keep my being utterly closed. She asked me to sign a document releasing the clinic from any responsibility. I signed quickly. This was not their mistake, it was mine.

She then informed me that because I was travelling alone and had to drive myself back to Canada, I would not be allowed to have any anaesthesia for the procedure. I could take a mild painkiller afterward, but that was all. Of course, I said. The threat of physical pain meant nothing in the moment. I left the meeting and was prepped for the surgery. There were many girls in that office, slotted back to back. Wheeled in, wheeled out. I don’t know what I had expected, perhaps candles and plush curtains, wise women wearing velvet robes, I don’t know. But the clinical coldness was a perfect match to the absolute block of ice in my own core.

What follows now in my story is not easy for me to express with words, but I will try, because it is something I feel needs to be said, shared and discussed. I have not seen my experience addressed in any of the opinion pieces currently flooding the media as the world reels with the overturning of Roe v. Wade. I have watched as yet another question of the layered human soul becomes politicized, infusing both starkly simplified viewpoints with righteousness. I am watching as my social media feeds fill up with slogans, announcements of alliances and declarations of war. I don’t see anyone, not one voice speaking to the profound complexities of what to do with the inconvenient onset of human life.

This is not simply a question of viability, it is a question of life force essence, of the intention within incarnation, and the power of life and death found in every woman’s womb.

As I was wheeled into surgery I remember being surrounded by female nurses, with a male doctor at my feet. There were huge, glaring lights overhead. I wondered why there were so many nurses. Dropping into the exhaustion of inevitability, I felt like a fly upside down on a table. I don’t remember being spoken to directly. I was made to open my legs, very wide, to this strange, masked doctor. I don’t remember the dreaded speculum. I don’t remember the dilation of the cervix. My memory of this moment always jolts into place with the sound of a pump positioned to one side of the doctor. A nurse told me it would hurt for a minute but then it would all be done. He had put the tentacle of the machine inside me, into the heart of me. Into a part of me that was unspeakably tender with new life, and then it began.

I was no stranger to pain. An accident prone and somewhat sickly child, I had suffered numerous broken bones and illnesses for most of my life. What happened to me was not just pain. Pain I could handle. In fact I was good at being brave in the face of pain. But this was the sensation of attack, the sudden shock of a profound violation as the connection to the vulnerable life force within me was ripped away. It may be that my sensitive nature allowed me to feel what others may not. All I know is that in every cell of my being I suddenly felt the terrible death of the being who had chosen my body and soul.

As the doctor began the suction process, all the denial, all the frozen, dissociated, disbelieving parts of my psyche woke up simultaneously. Something indescribably delicate and yet infinite was being killed inside of me, and that was the pain I felt. I was at one with the murder. This was not an awareness within my mind, but a visceral, stunning experience of betrayal taking place inside my physical body. I had not let myself feel any presence inside of me until that moment, and in a heartbeat, that moment became a terrible butchery, a brutal death. It was a nightmare beyond description, even now.

My body reacted immediately and uncontrollably as I lurched into an explosive defence. I fought with every ounce of strength I had to get off that table. I tried to kick the doctor, to kick the machine in his hand, to strike anything and everyone around me. Suddenly I understood why so many nurses, as they sprang into action and took hold of me, pinning me into place, trying to talk me down over top of my screams. The table beneath me lurched and chaos reigned. The doctor barked out orders. I screamed louder. I was sure I was dying, because if the purity within me was dying, I would go too. I later came to realize that it was a moment of recurring trauma which catapulted me across timelines and lifetimes, into a soul history of torture, a kind of torture only women can know.

I don’t remember how long this went on. I remember the doctor struggling, then giving up, sounding angry. I remember being allowed to have my legs back, to close them. After my sobs weakened, I was wheeled into a post op room full of girls on gurneys. Most were still sedated and only one other girl was crying. They were mostly sleepy and peaceful. Getting ready to go home with their mothers. Fellini was still in the air.

I don’t remember anyone speaking to me afterward. I don’t remember how I got to my car, or how I drove. I stopped at a pharmacy for Tylenol, walking with a body on fire.

I finally arrived home and crawled bleeding into bed. There was no sleep. By daylight I had a fever of 103. I called the clinic. They hurried me off the phone, saying there was nothing they could do as I was out of their jurisdiction. The nurse said they could send a prescription to a pharmacy for a drug that would address the infection. Then she whispered into the phone, the prescription will tell you to take it for three weeks, but only take it for a few days at most. It’s a terrible drug, toxic, in fact they are talking about taking it off the market and it will mess with you. Don’t take any more than you have to. I said thank you and hung up.

Weaker and sicker every hour, I willed myself to get into my car and drove to the nearest hospital. I had not been to this one before, but it was close and I found it, staggering into the emergency. They put me on a bed in a dark, cold room to be examined. I lay alone, my belly and loins in agony, and I wept.

A nurse entered the room and looked at me kindly, the way you would look at a frightened child, asking why was I crying, was I afraid to be examined. I almost laughed, but simply said no. Then a tall doctor, his presence as cold as the room, pushed through the door and went to the foot of the examining table. He asked me what was wrong, and now I finally had to say the words. He turned his face away and became even more silent. What I didn’t know at the time was that I had driven myself to a Catholic hospital, staffed with many Catholic physicians. Without further discussion, once again, my legs were thrown open wide.

Because of my fight to escape the machine at the clinic, the abortion was incomplete. Parts of the dead embryo were left inside me and a serious infection had quickly taken hold. I felt that I might be dying, and indeed, without medical care, I would have. And then, in that shadowy cold room, this large man between my legs thrust his gloved hand deep inside me without warning. He rammed his fingers into me with such force that my whole body slid inches up the table. I screamed and turned my eyes to the nurse who stepped back against the wall, gasping audibly, a look of helpless horror on her face. She stared at me with shock, but said, and did nothing.

He finally stopped, withdrew his hand and looked at my face for the first time. You have a serious infection he said. You are very ill and will likely be left with extensive scarring. You could have died, he said. You will likely not be able to have children, ever, he said. Of course, I thought. I allowed life to be pulled from my body, divine union torn apart. I cannot even kill properly, I thought. My loss was meant to be layered, drawn out, and infinitely deep.

The doctor instructed the nurse to schedule me for a D&C and they left the room, leaving me alone with Fellini.

During my hospital stay, I told only my parents and one close friend. They kept a suitable distance from my grief and shame. The hospital sent a chipper counsellor to my room, but we said little. I wanted to tell her that I was beyond hope, but that someone needed to talk to all those young girls being wheeled in and wheeled out of that clinic, the ones who kept their blocks of ice deeply frozen. They hadn’t felt the death, because they hadn’t yet let themselves feel the life. Why didn’t anyone tell them. Why didn’t anyone tell me.

I recovered in time. I went on with my life in a muted way, but something changed deep within me. An innocence, and a sense of personal permission was lost that day.

I did go on to marry and have three children, each one an immeasurable gift. But my way forward was never easy.

When my firstborn was three, I was pregnant again, and quite far along when I suffered a strong electrical shock from a short in our kitchen stove. I remember that day vividly too, the slicing pain of the shock, then falling back against the kitchen wall and sliding to the floor. I crouched there on the floor, sobbing, for some time, filled once again with overwhelming grief and fear. This too, this too must have been my fault.

There seemed to be no immediate effect, and for a time I entered my familiar numbness. I had been dreaming, and it would all be fine. At twenty-six weeks gestation I went to a routine check up with my team of midwives. I watched as one of them, a sweet and serious woman, listened through her stethoscope to my baby’s heartbeat. She then quietly excused herself and returned with her partner. This midwife then took a turn, checking and checking again, until they both sat and looked at me in silence. Finally one of them spoke. There is no heartbeat, they said. Do you understand, they said.

There was no way of knowing if the electric shock had caused my baby to die. In a way, it didn’t really matter.

Once again, I was cast into the hell realm of waiting. The ideal was for me to go into spontaneous labour and birth the baby naturally. So I was left to go about my life, carrying my dead child within me. It was perfect, absolutely perfect. Some will use the word karma to explain this rare punishment, but I will not. Karma is no expression of vengeance ever, but rather it is our loving teacher. Our blessings and our sufferings are not at war with one another, but rather lead us to the same place, that same field, that same desert plain.

When my body refused to give up its treasure and the risk of infection became too great, I was scheduled for a procedure. I was given a choice. One option was to be induced and go through a labour of extreme pain. Inductions are always more painful than natural labour, but with a deceased baby, the necessary hormones which would otherwise assist the labour are missing. I was told to expect extreme, almost unbearable pain.

My second option was another surgery, to cut up and remove the baby. Again my courage failed me and I chose to sleep through my loss. In preparation for the operation I was given an ultrasound which left the technician staring in fascination at the screen. Then I was told there would be a second ultrasound, and this time a dozen medical students flooded my room. Apparently my body had begun to reabsorb my baby, something common in other mammals, but rarely seen in humans and I was a ripe teaching moment for a gaggle of interns. I do not recall my permission being requested. I lay on the bed, images of my womb on display like a drive-in movie, as my body refused to relinquish my child.

I had stopped crying some time ago. I was at home with Fellini now.

As I was wheeled in for surgery, I asked the doctor if he could please tell me if the baby was a boy or a girl. He muttered that he wasn’t sure that would be possible. I knew she was a girl. When I was back in my room after the surgery I stood up for the first time to use the washroom, and looked at my soft belly in the mirror. I told myself, my child is gone, but I could not connect with how this had happened. My soul was once again numb.

I became ill several months later with a routine of waking at 3 am to terrible pain in my solar plexus, vomiting for hours. After many nights of lying on the bathroom floor, finally unable to stop vomiting, I ended up in hospital once again. There is nothing wrong with you, they told me, and sent me home. Could it be grief, the midwives asked me, as I lived yet another layer of my soul’s dance with children born and children lost.

I went on to have two more children, one born a year later, after a twenty minute labour. His was an unattended home birth, born in a bathtub before the midwives could get there, so much of a hurry was he in to make his presence known. Once again, I thought I was dying, but that is a story for another day.

When my youngest, my daughter, was a toddler, she was in the bath one day and looked up at me. Mommy, she said, I was in your belly before, but I had to go away. It made me very sad. To this day, my beautiful, radiant daughter hates to look at photos of her birth, even though they are far from graphic. From the time she was tiny she has said she will never give birth, and would rather adopt. She says it’s because those photos are too painful to see. I think there may be more to her story than that.

But what I have written here is my story, no one else’s, unique to my karmic path. I know many women who have had abortions without incident. I also know women who have had abortions and said, never again; whatever soul connects with mine, I will accept the experience, no matter the circumstance. This was so for me, for the balance of my fertile years. Whatever life brought to me was my experience to live.

Now that I have shared this story, for the first time ever, I must tell you dear reader, I will never say I am “pro life”. I dislike such terms, such attempts to minimize the complexity of what it means to be a woman and bear this gift, this responsibility. I profoundly honour the power of my capacity as a woman to house a spark of life in my body, and I will not relinquish this, not to the doctors who are care-less, not to the politicians who use the suffering of others to feed their ambitious hearts. There is no one on either side of this debate who desires the murder of a new life, as we suggest when we use such terms.

I also choose not to take a blanket, “pro choice” stance, which really means in the vast majority of cases, pro abortion. I refuse to minimize the complexity of this question, no matter how unpopular such a position may be. If we women are given the capacity for magic within our own bodies, we must also be prepared to tell the truth about the seriousness of our dilemmas, and this cannot be done within the framework of our present unconscious social schisms. To campaign to make abortion as readily available as a takeout meal is to be blind to the profound questions at the root of human incarnation. Abortion is already being used as a form of birth control by some women, and many questionable practices take place in abortion clinics. Late stage abortion is an unimaginable brutality.

At the same time, to deny legal abortion is to throw many women into exactly the kind of position in which I found myself forty years ago, having to drive distances and take risks in the midst of the heartbreak. For some, their situations are much, much worse than mine. To outright deny access to abortions will also to ensure the deaths of the many women who will continue to attempt to self-abort in dangerous circumstances, because their lives seem to give them no choice. Never has there been a greater Catch 22. Never has there been such widespread denial of what is really at stake.

Another vast question is, what about the role of the father of the unborn child? His escape from the responsibility of bodily ownership may seem to let him off the hook, but it also means that he may become completely powerless to voice his desires about his unborn child. What he believes and feels about her choice is popularly considered none of his business, yet it is a grave assumption to suggest that all men are happy to look the other way. I know of one couple whose full-term child was born with a birth defect, and the mother did not want to keep the child. It was the father who said, I will raise this child no matter what. Even if I have to leave you, this child is mine, imperfections and all. It was her body, but his strength at a critical moment which gave that baby a life and home.

After all I have experienced, what do I believe?

Abortion simply cannot be addressed as a solitary issue. It is inextricably braided with our historic misunderstanding of female sexual expression and widespread trauma, the lack of care and support of mothers and babies by their communities and nations, and the isolation induced by the mechanization and materialization of modern life.

We live in a time of great confusions, wherein titillation is mistaken for liberation and the true deep pleasure of life force expression has been replaced by transitory fads and addictions. The loss of authentic ownership of feminine essence has led to many broken, shallow lives, and all the pain which comes with disconnection from self.

One example of how cultural issues have created this tragically widespread solution to the unborn may be found in its polarity, with the Mosuo people, a matrilineal culture residing near the Tibetan Himalayas. Here girls are encouraged to be as sexual as boys, but from a place of pure acceptance; no pouty-lipped, twerking TikTok performances to be found. For the Mosuos, all sexual partners are mutually chosen, and discretion is offered to every young woman. No one intrudes upon her choices, and they practise “walking marriage” with no expectation of monogamy.

One might think that such a culture would be overflowing with teenage pregnancies and unwanted children, but in fact the opposite is so. For the Mosuos, there are no orphans and crime is almost unheard of. Girls rarely conceive at a young age, because girls have permission to access and choose a natural sexual expression, when they are ready and on their own terms. There is no marriage, and so no divorce. When children come they are raised communally in the matriarch’s home. The father supports the child, as do the brothers of the mother. Life, love and responsibility are entwined through the respect and the honouring of the feminine.

Given that such practices are so foreign to most of the world, we must acknowledge that we can hardly attempt to find an answer to abortion if we cannot begin to look honestly at the link between conception and healthy sexuality, for women and for men.

What does it mean to say that to kill an unborn child is murder? Is murder only the taking of human life? Do we murder our pets to ease their suffering when their health deteriorates? Do we murder when we execute prisoners on death row? Do we murder our enemy in war?

Do we murder the chickens and cows on our plates? Do we lobby for murder when we support assisted suicide? Do we murder when we cull wildlife, eradicate pests, leave roadkill on the highway behind our cars?

We do, and though it is a charged and sensationalized word, it simply means to intentionally take a life. So if we cannot change the meaning of the word, then we must begin to confront a deep and graceful truth, which is that death is an aspect of every life, and we must not look away. It is a part of life to participate in death, and to cause death may be necessary at times, or even for the good. It may be that we must face an agonizing choice to proceed, but until we are willing to look truthfully at our choices, wisdom will be held at bay. When we use shame as a weapon, when we deny that a terrible middle ground exists, we ultimately perpetuate and magnify our collective pain.

Perhaps ultimately we are simply asked to face death always with love, even when it seems imposed upon us, even when it is a choice beyond the imagining of our hearts.

Above all, abortion is only secondarily a political issue. Because we structure our world into countries, states and provinces, because we enact laws which define medical practices, we fall into the tangled, unconscious mess of a political frame of reference. But ultimately, abortion is always, always, an essentially human decision of life and death. And though this life may be new, still a flicker of Source within a womb which said yes, this is your home, it is necessarily a spiritual question. Not religious, not legal, not medical. A question only understood fully by the consciousness of a woman who finds herself, even briefly, a mother.

In this my heart goes out to every woman, those who have conceived and lost, those who have yet to conceive, and those who have made a choice to bear another living soul, born through the portal of Creation which is the body of a woman. You are the conduits of human mystery, and one day the true honour of this gift will be known to all. Until then, let yourself feel and let yourself know. Trust that you are worthy and pure, no matter what voices of hate live in your own shadow.

It is through love that life, and the inevitable blessing of death, will once again be understood and treasured in our world.

Beyond ideas of righteousness and blame there is a desert plain, a field of purity and light. One day, we will meet one another there.

much love, Adi

A stunningly beautiful, heart-wrenching retelling of your story Adi. You so eloquently bring forth a point of view that as you mentioned, is rarely shared. It's an important one, that casts away the over-simplification of an intensely layered experience where righteousness has no place, no matter the sentiment expressed by the one holding the placard. I stand with you in that uncomfortable middle ground, where more often than not, I find myself on these kinds of issues. One day I pray that all will be revealed, but I doubt very much that such clarity will come from earthly beings. Thank you for your thoughtful insight and bravery here.

Thank you, Adi, for your courage in sharing the story of your experience... and placing it into a broader, more nuanced context than "pro-this or anti-that".

There is more I want to say and share with you... another time... 💜🙏🏼💜