Dear Reader;

The passing of Queen Elizabeth II is a profound turning point. She was loved and she was hated, a figure of extraordinary stature. She was the last great monarch of another world.

May I tell you stories?

I was born Cynthia Long, of English and Cornish stock, with a dollop of Irish on the side. My mother was homesick for Cornwall and so when I was very young, we visited her childhood home in Perranporth, a soul-familiar land.

Cornwall then was pristine, with tragic, heathery cliffs and unpopulated beaches stretching into the horizon. We stayed in an old stone house by the sea with my great aunt and uncle, and slept in the same bedroom in which my mother and grandmother had been born.

I was awakened at sunrise by the clatter of horses traversing the winding street, on their way to work from a neighbouring stable. As guests we were served tea in bed in the morning. Each day a delivery boy brought fresh milk to the back door, and clotted Devon cream to melt on a hot scone with homemade jam. We ate, we walked, we paddled in the pools and slid down the giant dunes of sand.

Family.

My great uncle George kept a huge garden where I was allowed to steal fresh peas. He had built a tiny shed right smack in the middle of the vegetable rows, to house his prize pump organ. He loved to sit in the shed and play to the cucumbers.

George was a kind Englishman with rosy cheeks and a kerchief tied over his head, a man who walked absolutely everywhere, wore shorts year round and brought groceries every week to a blind neighbour. He was also on the Sunday morning beach cleaning committee, spending hours combing that endless beach to collect trash and lost trinkets which he kept in a chest of drawers.

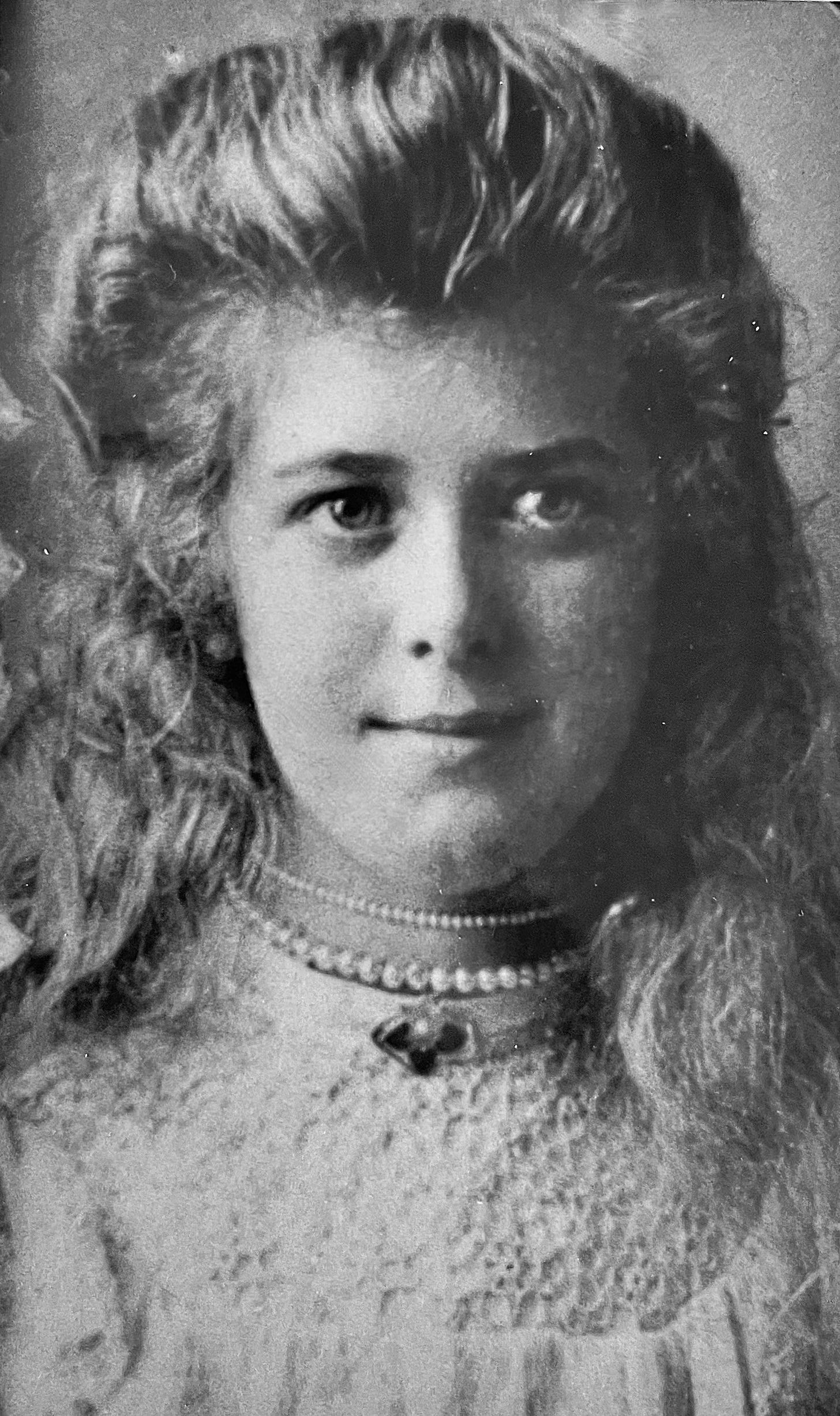

These were my people, and my mother, Vivien, was in every way an Englishwoman. It was in her blood, and she thought the world of her Queen. They even looked a little alike, and I could see the echoes of Elizabeth’s refined ways in my mother’s expressions and manner. My grandmother Lily Wearne had endured two world wars, the Great Depression, and an awful ocean journey to Canada, on her own with a young child. To her, the royal family represented loyalty and hope. Canada was a colony, but the Queen was home.

My grandmother’s father was a merchant who sailed to Africa in search of goods and on one trip he died there, leaving his entire family bereft but for a house full of African artifacts. What my Granny understood about British colonialism I will never know, but I can assuredly say she was one of the gentlest, kindest souls I have ever met. She was my safe haven as a child, living downstairs in a modest apartment filled with her porcelain cups, Underwood typewriter and volumes of Byron; a place where the BBC news played on the radio every day at noon, and tea was served to my grandfather promptly at four.

History.

I was a Canadian child, but what does that mean, in a world where ethnicities have begun to stack, shift and tumble like Jenga blocks. No real knowledge of Canada’s Indigenous was taught in my school, as we floated along in a naive haze. No one knew. No one could teach what was unspoken. Our only answers lived in the dog-eared, hand me down text books, and the Encyclopedia Brittanica.

Every year I waited for a teacher to answer the questions I held in my quiet heart. I was tired of studying about war and conquest. We were asked to memorize names and dates of battles and how many soldiers died, but I wanted to know about the women, the children, the animals left behind.

Growing up, a fair-skinned child of a British immigrant mother, I was given the middle name Eizabeth with a z. I read books of woodland fairies, a sheepdog named Shadow, and the adventures of children sent away to boarding school. My Granny sewed me soft cloth dolls and taught me English poetry. A few years later I discovered the Bronté sisters, reading my mother’s hardcover copies of Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre, the ones with gorgeous wood block print illustrations that gave me scary dreams. I saw the world through the lens of my heritage, my parents, and the qualities that made them who they were.

My mother was frugal but every Sunday night she made roast beef with horseradish and the scent of its slow cooking filled the house. It was the comforting smell of Sundays. At Christmas, she served a large trifle layered in a glass bowl with rum and English custard. I loved the custard and hated the rum. We grew up together as families do, shedding our unconscious ways little by little, morphing our selves with the changing times as the Beatles and the Kennedys invaded our home, from Levi’s to bellbottoms to my father’s velour track suits. We were just people growing as the world was growing. Each one of us, learning of love in our own way.

R-evolution.

My mother, as fierce and scary to me as the Queen herself, had a passion for helpless animals. Our home was always filled with four-leggeds, and she would make my father stop the car to pick up whatever creature was at the side of the road.

I am exactly the same. Queen Elizabeth so loved her dogs.

Once my mother came in from gardening in the backyard saying she couldn’t mow the lawn anymore because she heard the grass crying. My stern, bossy, untouchable mother wept with the grass.

I share these moments to say, I know a bit of who these Englishwomen were.

But now, as I write this on the death day of Elizabeth, on the eve of this September Harvest Moon in 2022, we walk in a time of revolution and revelation. A time when the dark underbelly of the powerful is being torn open before our eyes, and there are horrors to witness aplenty. It is almost too easy to do, our mouths dry with the bitterness of the cruelties we perceive, as we thirst for reckoning. When we scan the pages of the history we have unveiled, hand over hand with our ancestors and offspring; and as we call out each new misdeed as it becomes revealed, we lunge to tear down. We are hyenas who feast as the great beast falls.

Is it possible we have forgotten the purposeful nature of the evolution of the human spirit? Do we pull back in horror at the blindness of our foremothers, or do we witness their tragedies as experiences that have been lived by every soul along the journey. The teachings tell us, we have all been the victim and we have all been the perpetrator. We have all been asleep, and we are all born to awaken. I often wonder, would I have been any different, born into their time, their culture, into the arms of their parents’ world.

Off with her head.

A quick search online will spit up articles on the dark side of the Queen like lost valuables tossed upon my Great Uncle George’s beach. Her mistreatment and dismissal of Diana. Her cold emasculation of her husband. Her family’s ties to themes of sexual and ritual abuse. Some say she drank the blood of stolen babies for breakfast, alongside her scones and tea.

Every soul alive to witness the passing of Elizabeth has come here for a reason. Every one of us had the intention to be present for the deepest, the mightiest of upheavals in human history. We stand poised to watch the collapse of all the institutionalized systems. Religious, political, financial, medical, educational. If we look deeply enough into our hearts, instead of into the Encyclopedia Brittanica or even Google, we will discover that a great cleanse is underway, and the mighty are indeed falling. But does this make devils out of all men? Does this mean all that was good, human and beautiful must also be lost, baby thrown out with the righteous bathwater, in the collapse of the false and the birth of the real?

Every student of literature, every therapist, poet, every scholar of myth and dream knows that we walk within an archetypal world. It is clear to me that we also walk the stage of our own human theatre, dressed in the costume of our birth, each and every birth, time after time.

Elizabeth was no mistake. I am no mistake. Neither are you.

Each time we are born, prince or pauper, man or woman, conqueror or slave, we come with our own personal purpose interwoven within the threads of our material incarnation. None of these choices are in error. None of these experiences are wrong. None will be met with either reward or punishment, for each serves as foil to the other. And we each have the opportunity to know all kinds of lives, in turn.

Some say we are ready for a world where queens and kings are obsolete. A world where there is no place for pageantry and palaces, for crowns, castles and fairytale weddings. But when we know what we know, that all souls dance with intention, in partnership, perhaps it also does not serve us to idolize the end of our perceived polarities. In our search to answer the suffering of the people, we forget that while we are all worthy, we are never the same; are not meant to be and would not want to be, should such an experience be possible. It is the contrast which creates the parts of the whole; the many and the One.

How can we return to Oneness if we are too afraid to fully acknowledge our own separation? If we blame the villain, bleach the shadow and demand a happy ending, what would be the point of the story, after all?

Crowns.

There is a Queen in every woman, and a King in every man. Even the ones who remember the lives of the slaves know this. We all have a crown to wear, and a price to pay for such glory. These are the blessings of our kaleidoscopic, archetypal world and I for one would not want it any other way.

On behalf of my proud, English mother and sweet-hearted grandmother, I honour Elizabeth, the Queen of her people, a rare woman who gave everything in her life to the duties of her birth.

On behalf of my daughter’s unborn daughters, I honour what begins now, for in Elizabeth’s passing, an era has come to an end. At the tip of a culminating wave of fear and conflict, just as dark forces seem everywhere, she has made her mark and chosen her time. May she bless us as she leaves.

I choose to see what is revealed, and I choose to find the beauty everywhere. I choose to awaken my own crown, my own royalty, to be humbled before the interplay of illusion and love.

I choose to trust as the shadow rises and curls its tongue to kiss the birth light of a new world, a new day.

much love, Adi

Thank you